Home History and Culture

History and Culture

Antiquity

Armenia lies in the highlands surrounding the Biblical mountains of Ararat, upon which Noah's Ark is said to have come to rest after the flood. Recent archeological studies have found the earliest leather shoe, skirt, and wine-producing facility in Armenia, dated to about 4000 B.C.

This points to an advanced early civilization In the Bronze Age; several states flourished in the area of Greater Armenia, including the Hittite Empire (at the height of its power), Mitanni (South-Western historical Armenia), and Hayasa-Azzi (1500–1200 BC). The Nairi people (12th to 9th centuries BC) and the Kingdom of Urartu (1000–600 BC) successively established their sovereignty over the Armenian Highland. Each of the aforementioned nations and tribes participated in the ethno genesis of the Armenian people. Yerevan, the modern capital of Armenia, was founded in 782 BC by king Argishti I. Around 600 BC, the Kingdom of Armenia was established under the Orontid Dynasty. The kingdom reached its height between 95 and 66 BC under Tigranes the Great, becoming one of the most powerful kingdoms of its time within the region. Throughout its history, the kingdom of Armenia enjoyed periods of independence intermitted with periods of autonomy subject to contemporary empires. Armenia's strategic location between two continents has subjected it to invasions by many peoples, including the Assyrians, Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, Arabs, Mongols, Persians, Ottoman Turks and Russians. Armenia was historically Mazdean Zoroastrian (as opposed to the Zurvanite Sassanid dynasty), particularly focused on the worship of Mihr (Avestan Mithra), and Christianity spread into the country as early as AD 40. King Tiridates III (AD 238–314) made Christianity the state religion in AD 301, becoming the first officially Christian state, ten years before the Roman Empire granted Christianity an official toleration under Galerius, and 36 years before Constantine the Great was baptized. After the fall of the Armenian kingdom in AD 428, most of Armenia was incorporated as a marzpanate within the Sassanid Empire. Following an Armenian rebellion in AD 451, Christian Armenians maintained their religious freedom, while Armenia gained autonomy.

Middle Ages

After the Marzpanate period (428–636), Armenia emerged as the Emirate of Armenia, an autonomous principality within the Arabic Empire, reuniting Armenian lands previously taken by the Byzantine Empire as well. The principality was ruled by the Prince of Armenia, recognized by the Caliph and the Byzantine Emperor. It was part of the administrative division/emirate Arminiyya created by the Arabs, which also included parts of Georgia and Caucasian Albania, and had its center in the Armenian city Dvin. The Principality of Armenia lasted until 884, when it regained its independence from the weakened Arabic Empire . The re-emergent Armenian kingdom was ruled by the Bagratuni dynasty, and lasted until 1045 . In time, several areas of the Bagratid Armenia separated as independent kingdoms and princi palities such as the Kingdom of Vaspurakan ruled by the House of Artsruni, while still recogni zing the supremacy of the Bagratid kings. The Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, 1199-1375. In 1045 control as well. The Byzantine rule was short lived, as in 1071; Seljuk Turks defeated the Byzantines and conquered Armenia at the Battle of Manzikert, establishing the Seljuk Empire. To escape death or servitude at the hands of those who had assassinated his relative, Gagik II, King of Ani, an Armenian named Roupen went with some of his countrymen into the gorges of the Taurus Mountainsand then into Tarsus of Cilicia. The Byzantine governor of the palace gave them shelter where the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia was eventually established. Cilicia was a strong ally of the European Crusaders, and saw itself as a bastion of Christendom in the East. Cilicia's significance in Armenian history and statehood is also attested by the transfer of the seat of the Catholicos of the Armenian Apostolic Church, spiritual leader of the Armenian people, to the region.

The Seljuk Empire soon started to collapse. In the early 12th century, Armenian princes of the Zakarid noble family established a semi-independent Armenian principality in Northern and Eastern Armenia, known as Zakarid Armenia, lasted under patronages of Seljuks, Georgian Kingdom, Atabegs of Azerbaijan and Khwarezmid Empire. The noble family of Orbelians shared control with the Zakarids in various parts of the country, especially in Syunikand Vayots Dzor.

After the Marzpanate period (428–636), Armenia emerged as the Emirate of Armenia, an autonomous principality within the Arabic Empire, reuniting Armenian lands previously taken by the Byzantine Empire as well. The principality was ruled by the Prince of Armenia, recognized by the Caliph and the Byzantine Emperor. It was part of the administrative division/emirate Arminiyya created by the Arabs, which also included parts of Georgia and Caucasian Albania, and had its center in the Armenian city Dvin. The Principality of Armenia lasted until 884, when it regained its independence from the weakened Arabic Empire . The re-emergent Armenian kingdom was ruled by the Bagratuni dynasty, and lasted until 1045 . In time, several areas of the Bagratid Armenia separated as independent kingdoms and princi palities such as the Kingdom of Vaspurakan ruled by the House of Artsruni, while still recogni zing the supremacy of the Bagratid kings. The Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, 1199-1375. In 1045 control as well. The Byzantine rule was short lived, as in 1071; Seljuk Turks defeated the Byzantines and conquered Armenia at the Battle of Manzikert, establishing the Seljuk Empire. To escape death or servitude at the hands of those who had assassinated his relative, Gagik II, King of Ani, an Armenian named Roupen went with some of his countrymen into the gorges of the Taurus Mountainsand then into Tarsus of Cilicia. The Byzantine governor of the palace gave them shelter where the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia was eventually established. Cilicia was a strong ally of the European Crusaders, and saw itself as a bastion of Christendom in the East. Cilicia's significance in Armenian history and statehood is also attested by the transfer of the seat of the Catholicos of the Armenian Apostolic Church, spiritual leader of the Armenian people, to the region.

The Seljuk Empire soon started to collapse. In the early 12th century, Armenian princes of the Zakarid noble family established a semi-independent Armenian principality in Northern and Eastern Armenia, known as Zakarid Armenia, lasted under patronages of Seljuks, Georgian Kingdom, Atabegs of Azerbaijan and Khwarezmid Empire. The noble family of Orbelians shared control with the Zakarids in various parts of the country, especially in Syunikand Vayots Dzor.

Early Modern era

During the 1230s, the Mongol Empire conquered the Zakaryan Principality, as well as the rest of Armenia. Armenian soldiers formed an important part of the military of the Ilkhanate. The Mongolian invasions were soon followed by those of other Central Asian tribes (Kara Koyunlu, Timurid and Ak Koyunlu), which continued from the 13th century until the 15th century. After incessant invasions, each bringing destruction to the country, Armenia in time became weakened. During the 16th century, the Ottoman Empire and Safavid Persia divided Armenia among themselves. The Russian Empire later incorporated Eastern Armenia (consisting of the Erivan and Karabakh khanates within Persia) in 1813 and 1828. Under Ottoman rule, the Armenians were granted considerable autonomy within their own enclaves and lived in relative harmony with other groups in the empire (including the ruling Turks). However, as Christians under a strict Muslim social system, Armenians faced pervasive discrimination. When they began pushing for more rights within the Ottoman Empire, Sultan l-Hamid II, in response, organised state-sponsored massacres against the Armenians between 1894 and 1896, resulting in an estimated death toll of 80,000 to 300,000 people. The Hamidian massacres, as they came to be known, gave Hamid international infamy as the ;Red Sultan| or || Bloody Sultan |

During the 1230s, the Mongol Empire conquered the Zakaryan Principality, as well as the rest of Armenia. Armenian soldiers formed an important part of the military of the Ilkhanate. The Mongolian invasions were soon followed by those of other Central Asian tribes (Kara Koyunlu, Timurid and Ak Koyunlu), which continued from the 13th century until the 15th century. After incessant invasions, each bringing destruction to the country, Armenia in time became weakened. During the 16th century, the Ottoman Empire and Safavid Persia divided Armenia among themselves. The Russian Empire later incorporated Eastern Armenia (consisting of the Erivan and Karabakh khanates within Persia) in 1813 and 1828. Under Ottoman rule, the Armenians were granted considerable autonomy within their own enclaves and lived in relative harmony with other groups in the empire (including the ruling Turks). However, as Christians under a strict Muslim social system, Armenians faced pervasive discrimination. When they began pushing for more rights within the Ottoman Empire, Sultan l-Hamid II, in response, organised state-sponsored massacres against the Armenians between 1894 and 1896, resulting in an estimated death toll of 80,000 to 300,000 people. The Hamidian massacres, as they came to be known, gave Hamid international infamy as the ;Red Sultan| or || Bloody Sultan |

World War I and the Armenian Genocide

When World War I broke out leading to confrontation of the Ottoman Empire and the Russian Empire in the Caucasus and Persian Campaigns, the new government in Constantinople began to look on the Armenians with distrust and suspicion. This was because the Russian army contained a contingent of Armenian volunteers. On 24 April 1915, Armenian intellectuals were arrested by Ottoman authorities and, with the Tehcir Law (29 May 1915), eventually a large proportion of Armenians living in Anatolia perished in what has become known as the Armenian Genocide. There was local Armenian resistance in the region, developed against the activities of the Ottoman Empire. Armenians and the vast majority of Western historians to have been state-sponsored mass killings, or genocide regard the events of 1915 to 1917. Turkish authorities, however, maintain that the deaths were the result of a civil war coupled with disease and famine, with casualties incurred by both sides. According to the research conducted by Arnold J. Toynbee an estimated 600,000 Armenians died during the Armenian Genocide in 1915–16. According to the International Association of Genocide Scholars, the death toll was "more than a million". Armenia and the Armenian Diaspora have been campaigning for official recognition of the events as genocide for over 30 years. These events are traditionally commemorated yearly on 24 April , the Armenian Martyr Day, or the Day of the Armenian Genocide.

When World War I broke out leading to confrontation of the Ottoman Empire and the Russian Empire in the Caucasus and Persian Campaigns, the new government in Constantinople began to look on the Armenians with distrust and suspicion. This was because the Russian army contained a contingent of Armenian volunteers. On 24 April 1915, Armenian intellectuals were arrested by Ottoman authorities and, with the Tehcir Law (29 May 1915), eventually a large proportion of Armenians living in Anatolia perished in what has become known as the Armenian Genocide. There was local Armenian resistance in the region, developed against the activities of the Ottoman Empire. Armenians and the vast majority of Western historians to have been state-sponsored mass killings, or genocide regard the events of 1915 to 1917. Turkish authorities, however, maintain that the deaths were the result of a civil war coupled with disease and famine, with casualties incurred by both sides. According to the research conducted by Arnold J. Toynbee an estimated 600,000 Armenians died during the Armenian Genocide in 1915–16. According to the International Association of Genocide Scholars, the death toll was "more than a million". Armenia and the Armenian Diaspora have been campaigning for official recognition of the events as genocide for over 30 years. These events are traditionally commemorated yearly on 24 April , the Armenian Martyr Day, or the Day of the Armenian Genocide.

Democratic Republic of Armenia (DRA)

Although the Russian army succeeded in gaining most of Ottoman Armenia during World War I, their gains were lost with the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. At the time, Russian-controlled Eastern Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan attempted to bond together in the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic. This federation, however, only lasted from February to May 1918, when all three parties decided to dissolve it. As a result, Eastern Armenia became independent as the Democratic Republic of Armenia (DRA) on 28 May. Political divisions of Europe in 1919 showing the independent Armenian republic. The DRA's short-lived independence was fraught with war, territorial disputes, and a mass influx of refugees from Ottoman Armenia, spreading disease, and starvation. Still, the Entente Powers, appalled by the actions of the Ottoman government, sought to help the newly found Armenian state through relief funds and other forms of support. At the end of the war, the victorious Entente powers sought to divide the Ottoman Empire. Signed between the Allied and Associated Powers and Ottoman Empire at Sèvres on 10 August 1920, the Treaty of Sèvres promised to maintain the existence of the DRA and to attach the former territories of Ottoman Armenia to it. Because the new borders of Armenia were to be drawn by United States President Woodrow Wilson, Ottoman Armenia is also referred to as "Wilsonian Armenia." In addition, just days prior, on 5 August 1920, Mihran Damadian of the Armenian National Union, the de facto Armenian administration in Cilicia, declared the independence of Cilicia as an Armenian autonomous republic under French protectorate.

There was even consideration of possibly making Armenia a mandate under the protection of the United States. The treaty, however, was rejected by the Turkish National Movement, and never came into effect. The movement, under Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, used the treaty as the occasion to declare itself the rightful government of Turkey, replacing the monarchy based in Istanbul with a republic based in Ankara. Armenian civilians fleeing Kars after its capture by Kaz?m Karabekir's forces In 1920, Turkish nationalist forces invaded the fledgling Armenian republic from the east and the Turkish-Armenian War began. Turkish forces under the command of Kaz?m Karabekir captured Armenian territories that Russia annexed in the aftermath of the 1877–1878 years Russo-Turkish War and occupied the old city of Alexandropol (present-day Gyumri). The violent conflict finally concluded with the Treaty of Alexandropol (2 December 1920). The treaty forced Armenia to disarm most of its military forces, cede more than 50% of its pre-war territory, and to give up all the "Wilsonian Armenia" granted to it at the Sèvres treaty. Simultaneously, the Soviet Eleventh Army, under the command of Grigoriy Ordzhonikidze, invaded Armenia at Karavansarai (present-day Ijevan) on 29 November. By 4 December, Ordzhonikidze's forces entered Yerevan and the short-lived Armenian republic collapsed.

Although the Russian army succeeded in gaining most of Ottoman Armenia during World War I, their gains were lost with the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. At the time, Russian-controlled Eastern Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan attempted to bond together in the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic. This federation, however, only lasted from February to May 1918, when all three parties decided to dissolve it. As a result, Eastern Armenia became independent as the Democratic Republic of Armenia (DRA) on 28 May. Political divisions of Europe in 1919 showing the independent Armenian republic. The DRA's short-lived independence was fraught with war, territorial disputes, and a mass influx of refugees from Ottoman Armenia, spreading disease, and starvation. Still, the Entente Powers, appalled by the actions of the Ottoman government, sought to help the newly found Armenian state through relief funds and other forms of support. At the end of the war, the victorious Entente powers sought to divide the Ottoman Empire. Signed between the Allied and Associated Powers and Ottoman Empire at Sèvres on 10 August 1920, the Treaty of Sèvres promised to maintain the existence of the DRA and to attach the former territories of Ottoman Armenia to it. Because the new borders of Armenia were to be drawn by United States President Woodrow Wilson, Ottoman Armenia is also referred to as "Wilsonian Armenia." In addition, just days prior, on 5 August 1920, Mihran Damadian of the Armenian National Union, the de facto Armenian administration in Cilicia, declared the independence of Cilicia as an Armenian autonomous republic under French protectorate.

There was even consideration of possibly making Armenia a mandate under the protection of the United States. The treaty, however, was rejected by the Turkish National Movement, and never came into effect. The movement, under Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, used the treaty as the occasion to declare itself the rightful government of Turkey, replacing the monarchy based in Istanbul with a republic based in Ankara. Armenian civilians fleeing Kars after its capture by Kaz?m Karabekir's forces In 1920, Turkish nationalist forces invaded the fledgling Armenian republic from the east and the Turkish-Armenian War began. Turkish forces under the command of Kaz?m Karabekir captured Armenian territories that Russia annexed in the aftermath of the 1877–1878 years Russo-Turkish War and occupied the old city of Alexandropol (present-day Gyumri). The violent conflict finally concluded with the Treaty of Alexandropol (2 December 1920). The treaty forced Armenia to disarm most of its military forces, cede more than 50% of its pre-war territory, and to give up all the "Wilsonian Armenia" granted to it at the Sèvres treaty. Simultaneously, the Soviet Eleventh Army, under the command of Grigoriy Ordzhonikidze, invaded Armenia at Karavansarai (present-day Ijevan) on 29 November. By 4 December, Ordzhonikidze's forces entered Yerevan and the short-lived Armenian republic collapsed.

Soviet Armenia

Armenia was annexed by Bolshevist Russia and along with Georgia and Azerbaijan, it was incorporated into the Soviet Union as part of theTranscaucasian SFSR (TSFSR) on 4 March 1922. With this annexation, the Treaty of Alexandropol was superseded by the Turkish-Soviet Treaty of Kars. In the agreement, Turkey allowed the Soviet Union t o assume control over Adjara with the port city of Batumi in return for sovereignty ove r the cities of Kars, Ardahan, and Igdir, all of which were part of Russian Armenia. Th e TSFSR existed from 1922 to 1936, when it was divided up into three separate entities (Armenian SSR, Azerbaijan SSR, and Georgian SSR). Armenians enjoyed a period of relative stability under Soviet rule. They received medicine, food, and other provisions from Moscow , and communist rule proved to be a soothing balm in contrast to the turbulent final years of the Ottoman Empire. The situation was difficult for the church, which struggled under So viet rule. After the death of Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin took the reins of power and bega n an era of renewed fear and terror for Armenians. As with various other ethnic groups who lived in the Soviet Union during Stalin's Great Purge, tens of thousands of Armenians were ei ther executed or deported. Armenia was spared the devastation and destruction that wrought mo st of the western Soviet Union during the Great Patriotic War of World War II. The Nazis never r eached the South Caucasus, which they intended to do in order to capture the oil fields in Azerb aijan. Still, Armenia played a valuable role in aiding the allies both through industry and agricul ture. An estimated 500,000 Armenians, out of a population of 1.4 million, were mobilized. 175 000 of these men died in the war. Fears decreased when Stalin died in 1953 and Nikita Khruschev emerge d as the Soviet Union's new leader. Soon, life in Soviet Armenia began to see rapid improvemen t. The church, which suffered greatly under Stalin, was revived when Catholicos Vazgen I assume the duties of his office in 1955. In 1967, a memorial to the victims of the Armenian Genocide was built at the Tsitsernakaberd hill above the Hrazdan gorge in Yerevan. This occurred after mass dem onstrations took place on the tragic event's fiftieth anniversary in 1965. Armenians gat her at Theater Square in central Yerevan to protest Soviet policies and rule in 1988. Du ring the Gorbachev era of the 1980s with the reforms of Glasnost and Perestroika, Armenians began to demand better environmental care for their country, opposing the pollution that Soviet- built factories brought. Tensions also developed between Soviet Azerbaijan and its autonomou s district of Nagorno-Karabakh, a majority-Armenian region separated by Stalin from Armenia in 1923. The Armenians of Karabakh demanded unification with Soviet Armenia. Peaceful protest s in Yerevan supporting the Karabakh Armenians were met with anti-Armenian pogroms in the Az erbaijani city of Sumgait. Compounding Armenia's problems was a devastating earthquake in 198 8 with a moment magnitude of 7.2. Gorbachev's inability to solve Armenia's problems (especia lly Karabakh) created disillusionment among the Armenians and only fed a growing hunger for i ndependence. In May 1990, the New Armenian Army (NAA) was established, serving as a defense fo rce separate from the Soviet Red Army. Clashes soon broke out between the NAA and Soviet Internal Security Forces (MVD) troops based in Yerevan when Armenians decided to commemorate the establishm ent of the 1918 Democratic Republic of Armenia. The violence resulted in the deaths of five Armenia ns killed in a shootout with the MVD at the railway station. Witnesses there claimed that the MVD use d excessive force and that they had instigated the fighting. Further firefights between Armenian m ilitiamen and Soviet troops occurred in Sovetashen, near the capital and resulted in the deaths o f over 26 people, mostly Armenians. Pogrom of Armenians in Baku in January 1990 forced almost al l of the 200,000 Armenians in the Azerbaijani capital Baku to flee to Armenia. On 17 March 1991, Armenia, along with the Baltic states, Georgia and Moldova, boycotted a union-wide referendum in w hich 78% of all voters voted for the retention of the Soviet Union in a reformed form.

Restoration of independence

On 23 August 1990, Armenia declared independence, becoming the first non-Baltic republic to secede from the Soviet Union. When, in 1991, the Soviet Union was dissolved, Armenia's independence was officially recognized. However, the initial post-Soviet years were marred by economic difficulties as well as the breakout of a full-scale armed confrontation between the Karabakh Armenians and Azerbaijan. The economic problems had their roots early in the Karabakh conflict when the Azerbaijani Popular Front managed to pressure the Azerbaijan SSR to instigate a railway and air blockade against Armenia. This move effecti vely crippled Armenia's economy as 85% of its cargo and goods arrived through rail traffic. In 1993, Turkey joined the blockade against Armenia in support of Azerbaijan.

The Karabakh war ended after a Russian-brokered cease-fire was put in place in 1994. The war was a success for the Karabakh Armenian forces who managed to secure 14% of Azerbaijan's internationally recognized territory including Nagorno-Karabakh itself. Since then, Armenia and Azerbaijan have held peace talks, mediated by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). The status over Karabakh has yet to be determined. The economies of both countries have been hurt in the absence of a complete resolution and Armenia's borders with Turkey and Azerbaijan remain closed. By the time both Azerbaijan and Armenia had finally agreed to a ceasefire in 1994, an estimated 30,000 people had been killed and over a million had been displaced.

As it enters the 21st century, Armenia faces many hardships. Still, it has managed to make some improvements. It has made a full switch to a market economy and as of 2009, is the 31st most economic ally free nation in the world. Its relations with Europe, the Middle East, and the Commonwealth of Ind ependent States have allowed Armenia to increase trade. Gas, oil, and other supplies come through two v ital routes: Iran and Georgia. Armenia maintains cordial relations with both countries.

Armenia was annexed by Bolshevist Russia and along with Georgia and Azerbaijan, it was incorporated into the Soviet Union as part of theTranscaucasian SFSR (TSFSR) on 4 March 1922. With this annexation, the Treaty of Alexandropol was superseded by the Turkish-Soviet Treaty of Kars. In the agreement, Turkey allowed the Soviet Union t o assume control over Adjara with the port city of Batumi in return for sovereignty ove r the cities of Kars, Ardahan, and Igdir, all of which were part of Russian Armenia. Th e TSFSR existed from 1922 to 1936, when it was divided up into three separate entities (Armenian SSR, Azerbaijan SSR, and Georgian SSR). Armenians enjoyed a period of relative stability under Soviet rule. They received medicine, food, and other provisions from Moscow , and communist rule proved to be a soothing balm in contrast to the turbulent final years of the Ottoman Empire. The situation was difficult for the church, which struggled under So viet rule. After the death of Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin took the reins of power and bega n an era of renewed fear and terror for Armenians. As with various other ethnic groups who lived in the Soviet Union during Stalin's Great Purge, tens of thousands of Armenians were ei ther executed or deported. Armenia was spared the devastation and destruction that wrought mo st of the western Soviet Union during the Great Patriotic War of World War II. The Nazis never r eached the South Caucasus, which they intended to do in order to capture the oil fields in Azerb aijan. Still, Armenia played a valuable role in aiding the allies both through industry and agricul ture. An estimated 500,000 Armenians, out of a population of 1.4 million, were mobilized. 175 000 of these men died in the war. Fears decreased when Stalin died in 1953 and Nikita Khruschev emerge d as the Soviet Union's new leader. Soon, life in Soviet Armenia began to see rapid improvemen t. The church, which suffered greatly under Stalin, was revived when Catholicos Vazgen I assume the duties of his office in 1955. In 1967, a memorial to the victims of the Armenian Genocide was built at the Tsitsernakaberd hill above the Hrazdan gorge in Yerevan. This occurred after mass dem onstrations took place on the tragic event's fiftieth anniversary in 1965. Armenians gat her at Theater Square in central Yerevan to protest Soviet policies and rule in 1988. Du ring the Gorbachev era of the 1980s with the reforms of Glasnost and Perestroika, Armenians began to demand better environmental care for their country, opposing the pollution that Soviet- built factories brought. Tensions also developed between Soviet Azerbaijan and its autonomou s district of Nagorno-Karabakh, a majority-Armenian region separated by Stalin from Armenia in 1923. The Armenians of Karabakh demanded unification with Soviet Armenia. Peaceful protest s in Yerevan supporting the Karabakh Armenians were met with anti-Armenian pogroms in the Az erbaijani city of Sumgait. Compounding Armenia's problems was a devastating earthquake in 198 8 with a moment magnitude of 7.2. Gorbachev's inability to solve Armenia's problems (especia lly Karabakh) created disillusionment among the Armenians and only fed a growing hunger for i ndependence. In May 1990, the New Armenian Army (NAA) was established, serving as a defense fo rce separate from the Soviet Red Army. Clashes soon broke out between the NAA and Soviet Internal Security Forces (MVD) troops based in Yerevan when Armenians decided to commemorate the establishm ent of the 1918 Democratic Republic of Armenia. The violence resulted in the deaths of five Armenia ns killed in a shootout with the MVD at the railway station. Witnesses there claimed that the MVD use d excessive force and that they had instigated the fighting. Further firefights between Armenian m ilitiamen and Soviet troops occurred in Sovetashen, near the capital and resulted in the deaths o f over 26 people, mostly Armenians. Pogrom of Armenians in Baku in January 1990 forced almost al l of the 200,000 Armenians in the Azerbaijani capital Baku to flee to Armenia. On 17 March 1991, Armenia, along with the Baltic states, Georgia and Moldova, boycotted a union-wide referendum in w hich 78% of all voters voted for the retention of the Soviet Union in a reformed form.

Restoration of independence

On 23 August 1990, Armenia declared independence, becoming the first non-Baltic republic to secede from the Soviet Union. When, in 1991, the Soviet Union was dissolved, Armenia's independence was officially recognized. However, the initial post-Soviet years were marred by economic difficulties as well as the breakout of a full-scale armed confrontation between the Karabakh Armenians and Azerbaijan. The economic problems had their roots early in the Karabakh conflict when the Azerbaijani Popular Front managed to pressure the Azerbaijan SSR to instigate a railway and air blockade against Armenia. This move effecti vely crippled Armenia's economy as 85% of its cargo and goods arrived through rail traffic. In 1993, Turkey joined the blockade against Armenia in support of Azerbaijan.

The Karabakh war ended after a Russian-brokered cease-fire was put in place in 1994. The war was a success for the Karabakh Armenian forces who managed to secure 14% of Azerbaijan's internationally recognized territory including Nagorno-Karabakh itself. Since then, Armenia and Azerbaijan have held peace talks, mediated by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). The status over Karabakh has yet to be determined. The economies of both countries have been hurt in the absence of a complete resolution and Armenia's borders with Turkey and Azerbaijan remain closed. By the time both Azerbaijan and Armenia had finally agreed to a ceasefire in 1994, an estimated 30,000 people had been killed and over a million had been displaced.

As it enters the 21st century, Armenia faces many hardships. Still, it has managed to make some improvements. It has made a full switch to a market economy and as of 2009, is the 31st most economic ally free nation in the world. Its relations with Europe, the Middle East, and the Commonwealth of Ind ependent States have allowed Armenia to increase trade. Gas, oil, and other supplies come through two v ital routes: Iran and Georgia. Armenia maintains cordial relations with both countries.

History and Culture

Armenian History Armenia boasts one of the world’s oldest civilizations, with its history deeply intertwined with the development of culture, religion, and politics in the region.

Ancient Armenia

• Early Civilization: The Armenian Highlands have been inhabited since prehistoric times. By the 9th century BCE, the Kingdom of Urartu emerged, serving as a precursor to the Armenian state.

• Kingdom of Armenia: The Kingdom of Armenia was established in 331 BCE by Orontid rulers, followed by the Artaxiad dynasty. Under King Tigran the Great (95–55 BCE), it expanded to become one of the largest empires of the ancient world.

• Adoption of Christianity: In 301 AD, Armenia became the first nation to adopt Christianity as a state religion, under King Tiridates III and the influence of Saint Gregory the Illuminator.

• Medieval Armenia: The fall of the Armenian Kingdom to Byzantine and Persian empires led to periods of foreign domination. Despite this, Armenia maintained its cultural identity. Later History

• Cilician Armenia: During the 12th-14th centuries, the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia thrived as a hub for trade and diplomacy, particularly with European crusaders.

• Ottoman and Persian Rule: Armenia was divided between the Ottoman and Persian empires from the 16th century. This period brought hardships but also cultural preservation through the Armenian Church.

• Armenian Genocide: During World War I (1915-1917), the Ottoman Empire orchestrated the mass extermination of Armenians, resulting in the deaths of 1.5 million people and a vast diaspora.

• Modern Armenia: Armenia gained independence briefly in 1918, became part of the Soviet Union in 1920, and regained independence in 1991 after the Soviet collapse. Armenian Culture Armenia’s culture is a blend of ancient traditions, Christian influence, and a rich artistic heritage. Language and Literature

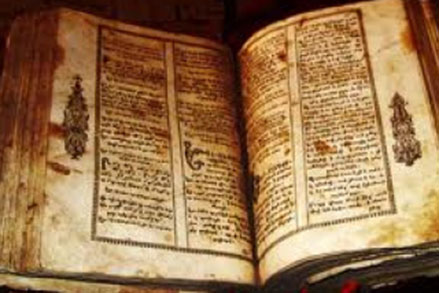

• Armenian Language: Unique and ancient, it uses an alphabet created by Mesrop Mashtots in 405 AD.

• Literature: Classical Armenian literature includes religious texts, epic poetry like “David of Sassoun,” and works by writers like Hovhannes Tumanyan. Art and Architecture

• Churches and Monasteries: Armenia is often called an “open-air museum” due to its numerous medieval monasteries and churches, such as Echmiadzin Cathedral, Geghard, and Noravank.

• Miniature Art: Medieval Armenian manuscripts are renowned for their intricate illuminations. Music and Dance

• Traditional Music: Instruments like the duduk, zurna, and kanun are central. The duduk, a UNESCO-recognized instrument, embodies the soulful spirit of Armenia.

• Folk Dance: Dances like Kochari are performed at festivals and weddings, reflecting Armenia’s communal spirit. Cuisine

• Rich in flavors, Armenian cuisine emphasizes fresh ingredients and traditional methods. Key dishes include:

• Lavash: Thin bread baked in a tandoor, recognized by UNESCO.

• Khorovats: Grilled meat (Armenian barbecue).

• Dolma: Stuffed grape leaves or vegetables.